Month: March 2019

Ibn Khaldun and the Rise and Fall of Empires

The 14th-century historiographer and historian Abu Zayd ‘Abd al-Rahman ibn Khaldun was a brilliant scholar and thinker now viewed as a founder of modern historiography, sociology and economics. Living in one of human kind’s most turbulent centuries, he observed at first hand, or participated in, such decisive events as the birth of new states, the disintegration of the Muslim Andalus and the advance of the Christian reconquest, the Hundred Years’ War, the expansion of the Ottoman Empire, the decline of Byzantium and the epidemic of the Black Death. Considered by modern critics as the thinker that conceived and created a philosophy of history that was undoubtedly one of the greatests works ever created by a man of intelligence, so groundbreaking were his ideas, and so far ahead of his time, that his writings are taken as a lens through which to view not only his own time but the relations between Europe and the Muslim world in our own time as well.

1. Introductory note by the editors of Saudi Aramco World

Abu Zayd ‘Abd al-Rahman ibn Muhammad ibn Khaldun al-Hadhrami, 14th-century Arab historiographer and historian, was a brilliant scholar and thinker now viewed as a founder of modern historiography, sociology and economics. Living in one of human kind’s most turbulent centuries, he observed at first hand—or even participated in—such decisive events as the birth of new states, the death throes of al-Andalus and the advance of the Christian reconquest, the Hundred Years’ War, the expansion of the Ottoman Empire, the decline of Byzantium and the great epidemic of the Black Death. Albert Hourani described Ibn Khaldun’s world as “full of reminders of the fragility of human effort”; out of his experiences, Arnold Toynbee wrote, “he conceived and created a philosophy of history that was undoubtedly the greatest work ever created by a man of intelligence.” So groundbreaking were his ideas, and so far ahead of his time, that a major exhibition [1] now takes his writings as a lens through which to view not only his own time but the relations between Europe and the Arab world in our own time as well.

|

|

Figure 1: A modern statue of Ibn Khaldun stands in the center of Tunis, his native city, on the Habib Bourguiba Avenue. Photography taken in July 2007. (Source). |

2. His Life

Ibn Khaldun’s ancestors were from the Hadhramawt, now southeastern Yemen, and he relates that, in the eighth century, one Khaldun ibn ‘Uthman was with the Yemeni divisions that helped the Muslims colonize the Iberian Peninsula. Khaldun ibn ‘Uthman settled first at Carmona and then in Seville, where several of the family had distinguished careers as scholars and officials.

During the Christian reconquest of the Iberian Peninsula, the family emigrated to North Africa, probably about 1248, eventually settling in Tunis. There Ibn Khaldun was born on May 7, 1332. He received an excellent classical education, but when he was 17, the plague, or Black Death, reached the city. His parents and several of his teachers died. The terrible epidemic that struck the Middle East, North Africa and Europe in 1347–1348, killing at least one-third of the population, had a traumatic effect on the survivors. Its impact showed in every aspect of life: art, literature, social structures and intellectual life. It was clearly one of the experiences that shaped Ibn Khaldun’s perception of the world.

Tunis was not only ravaged by the Black Death, but had also been reduced to political chaos by its occupation between 1340 and 1350 by the Marinids, the Berber dynasty that ruled Morocco. At 20, Ibn Khaldun set out for Fez, the Marinid capital, the liveliest court in North Africa. On the strength of his education, he was offered a secretarial position, but left before long. Although some historians regard his departure as disloyal, it is more likely he was fleeing the general political disintegration.

This was to be a pattern in Ibn Khaldun’s life. He was constantly tempted to become involved in murky political intrigues which, combined with the extreme instability of most of the ruling dynasties, meant that he had little choice but frequent changes of master. These experiences, like those of the Black Death, were instrumental in shaping his outlook.

|

|

Figure 2: Miniature “Victimes de la peste de 1349” (victims of 1349-plague) in the Annales of Gilles le Muisit (1272-1353). The Great Plague, or Black Death, swept from Central Asia to Europe, killing an estimated one-third of the population wherever it spread. It reached Tunis in 1348 when Ibn Khaldun was 17; its victims included his parents and several of his teachers. These losses, together with the ensuing social and economic chaos, deeply affected him. © Royal Library of Belgium. (Source). |

After a number of moves, he found himself back in Fez, where the previous Marinid ruler had been supplanted by his son, Abu ‘Inan, to whom Ibn Khaldun offered his services. Soon, however, he was once again caught up in political turmoil, and after many changes of fortune, including two years in prison, he decided to withdraw to Granada in 1362. The roots of this decision went back several years.

In 1359, the ruler of Granada, Muhammad ibn al-Ahmar, had been forced to flee to Fez together with his vizier, Ibn al-Khatib, one of the most famous scholars of the age. There they had met Ibn Khaldun. A warm friendship had developed, so that when, in turn, Ibn Khaldun had to escape from similarly dangerous politics, he was received in Granada with honors. Two years later, in 1364, Ibn Khaldun was sent by Ibn al-Ahmar to Seville on a peace mission to King Pedro I of Castile, known as “Pedro the Cruel.” In his Autobiography (Ta‘rif), Ibn Khaldun describes how Pedro offered to return his family estates and properties to him, and how he refused the offer. This contact with a Christian power was another watershed experience. He reflected not only on his own family’s past, but also on the changing fate of kingdoms—and above all on the historical and theological implications of the reassertion of Christian power in Iberia after more than five centuries of Muslim hegemony.

Later, personal clashes with Ibn al-Khatib, probably fueled by a mixture of jealousy and court intrigue, drove Ibn Khaldun back to the turmoils of North Africa. He had repeatedly expressed the wish to devote his life to scholarship, but the political world clearly fascinated him. Over and over he succumbed to its temptations; in any case, so well-known a figure was unlikely to be left in peace to study.

In spite of their differences, Ibn Khaldun continued to correspond with Ibn al-Khatib, and several of these letters are cited in his Autobiography. He also tried to save his friend when, largely as a result of court intrigue, Ibn al-Khatib was brought to trial, accused of heresy for contradicting the ‘ulama, the religious authorities, by insisting that the plague was a communicable disease. His situation can be compared with that of Galileo nearly three centuries later, but with a less happy outcome: Ibn al-Khatib was strangled in prison at Fez in the late spring of 1375.

Ibn Khaldun was much affected by his friend’s death, not only personally, but also because of the political and religious implications of such an execution. Not long afterward, he withdrew to the Castle of Ibn Salamah, not far from Oran in Algeria. There, for the first time, he could really dedicate himself to study and reflect on what he had learned from books, as well as on his often bitter experience of the violent and turbulent world of his day.

The fruit of this period of calm was the Muqaddimah or Introduction to his Kitab al-‘Ibar (The Book of Admonitions or Book of Precepts, also often referred to as the Universal History.) Although these are really one work, they are often considered separately, for the Muqaddimah contains Ibn Khaldun’s most original and controversial perceptions, while the Kitab al-‘Ibar is a conventional narrative history. Ibn Khaldun continued to rewrite and revise his great work in the light of new information or experience for the rest of his life.

He spent the years from 1375 to 1379 at the Castle of Ibn Salamah, but at last felt the need for intellectual companionship—and for proper libraries in which to continue his research. At the age of 47, Ibn Khaldun returned again to Tunis, where “my ancestors lived and where there still exist their houses, their remains and their tombs.” He planned to travel no more and to settle down as a teacher and scholar, eschewing all political involvement.

That was not so easy. Some considered his rationalist teachings subversive, and the imam of al-Zaytunah Mosque in Tunis, with whom he had been on terms of rivalry since his student days, became jealous. To make matters yet more difficult, the sultan insisted that Ibn Khaldun remain in Tunis and complete his book there, since a ruler’s status was greatly enhanced by attracting learned men to his court.

The situation finally became so tense and so difficult that in 1382 Ibn Khaldun asked permission to leave to perform the hajj, the pilgrimage to Makkah—the one reason for withdrawal that could never be denied in the Islamic world. In October he set out for Egypt. He was immensely impressed by Cairo, which exceeded all his expectations. There, the Mamluk sultan Barquq received him with enthusiasm and gave him the important position of qadi, or justice, of the Maliki school of Islamic law.

This, however, proved to be no sinecure. In his Autobiography, Ibn Khaldun describes how his efforts to combat corruption and ignorance, together with the jealousy aroused by the appointment of a foreigner to a top job, meant that once again he found himself in a hornets’ nest. It was something of a relief when the sultan dismissed him in favor of the former qadi. In fact, before the end of his life, Ibn Khaldun was to be appointed and dismissed no fewer than six times.

Ibn Khaldun was married and had children; he had a sister who died young—her tombstone survives—and his brother Yahya ibn Khaldun was also a very distinguished historian. However, we know very little about his personal life. It was not the Muslim, and in particular not the Arab, custom to include personal details in one’s writings. We do know, however, that at about this time, Ibn Khaldun’s family and household, which was essentially being held hostage at Tunis for his return, were given permission to join him in Cairo. This was at the personal request of Barquq, whose letter is quoted in the Autobiography. But the boat carrying his family went down in a tempest off Alexandria, and no one survived.

Three years passed. Ibn Khaldun dedicated himself to teaching and then at last set out to perform the hajj in 1387 with the Egyptian caravan. Ibn Khaldun says little of his pilgrimage, but he mentions that at Yanbu‘ he received a letter from his old friend Ibn Zamrak, many of whose poems are inscribed on interior walls of the Alhambra. Ibn Zamrak, then the confidential secretary of the ruler of Granada, asked among other things for books from Egypt. It is one more example of how Ibn Khaldun maintained his intellectual contacts all across the Arabic-speaking world.

On his return to Cairo, Ibn Khaldun held various teaching posts, but from 1399 the cycle of political appointments and dismissals began again. The scholar had already witnessed at first hand the political upheavals caused by the various Berber dynasties in North Africa, as well as the success of the Christian powers in reducing the Muslim kingdoms in the Iberian Peninsula. Now he was about to witness another example of the rise and fall of empires, this time with an epicenter farther to the east than he had ever traveled.

|

|

Figure 3: Astrolabic quadrant made by Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Mizzi the the muwaqqit (time-keeper) of the Great Mosque of Damascus in 1333-34 CE. There are four other astrolabic quadrants signed by the same craftsman, and they are the earliest known examples of this type of quadrant. (Source). |

In 1400, Ibn Khaldun was compelled by Barquq’s successor, Sultan al-Nasir, to travel to Damascus, where he took part in the negotiations with the Central Asian conqueror Timur, the Turco-Mongol ruler known in the West as Tamerlane. The aim was to persuade Timur to spare Damascus. Ibn Khaldun describes his conversations with Timur in some of the most interesting pages of his Autobiography.

In the end, however, the Egyptian diplomatic delegation was unsuccessful. Timur did sack Damascus and from there went on to take Baghdad, with great loss of life. The following year, Timur defeated the Ottomans at Ankara, taking their Sultan Beyazit prisoner. These events are described by the Spanish traveler Ruy Gonzáles de Clavijo, who went out to Samarkand in 1403 as ambassador to Timur.

Ibn Khaldun’s Autobiography continues for no more than a page or two after his return from Damascus, and he mentions only his appointments and dismissals. Although he never returned to Tunis, he continued to think of himself as a westerner, wearing until the last the dark burnous that is still the national dress of North Africa. He continued to revise and correct his great work until his death in Cairo on March 16, 1406—600 years ago this past spring.

3. His Work

Ibn Khaldun’s most important work was Kitab al-‘Ibar, and of that the most significant section was the Muqaddimah. Such “introductions” were a recognized literary form at the time, and it is thus not surprising that the Muqaddimah is both long—three volumes in the standard translation—and the repository of its author’s most original thoughts. Kitab al-‘Ibar, which follows, is much more conventional in both content and organization, although it is one of the most important surviving sources for the history of medieval North Africa, the Berbers and, to a lesser extent, Muslim Spain.

In the early 19th century, western scholars, already admirers of such Muslim thinkers as the philosopher Ibn Rushd, whom they knew as Averroes, became aware of the Muqaddimah, probably through the Ottoman Turks. They were struck by its originality—all the more so because it was written at a time when political and religious authority were exerting increasing pressure against independent thought, resulting in a decline of original scholarship. In this context, Ibn Khaldun’s interest in a whole range of subjects that today would be classified as sociology and economic theory, and his wish to create a new discipline to accommodate them, came as a particular surprise to scholars in both the Arab world and the West.

Many of the subjects that Ibn Khaldun discusses are not, however, new preoccupations. They had also concerned both Greek thinkers and earlier Arab writers, such as al-Farabi and Mas‘udi, to whom Ibn Khaldun refers frequently. The question of how much access Ibn Khaldun had to Greek sources in translation is still being debated, and in particular whether he had read Plato’s Republic. But Ibn Khaldun’s originality lies not in the fact he was conscious of these problems, but in his awareness of the complexity of their interrelationships and the need to study social cause and effect in a rigorous way.

|

|

Figure 4: One of the many beautiful patios of the Alcazar palace in Seville showing the delicately carved arches of the Patio del Yeso (Patio of the Stuccoes). In 1364, Ibn Khaldun journeyed to Seville, seat of the Castillan monarch Pedro I, whose magnificent Real Alcázar (“Royal Palace”), inspired from Mudejar art, was then close to completion. (Source). |

It is in this way that Ibn Khaldun took his place in a chain of intellectual development. Although his work was not followed up by succeeding generations, and indeed met with some disapproval and even censure, the great Egyptian historian al-Maqrizi perhaps chose his career as a result of his acquaintance with Ibn Khaldun, and he developed some of Ibn Khaldun’s ideas. It was, however, the Ottoman Turks who took the most interest in his theories concerning the rise and fall of empires, since many of the points he discusses appeared to apply to their own political situation.

In the Muqaddimah, Ibn Khaldun’s central theme is why nations rise to power and what causes their decline. He divides his argument into six sections or fields. At the beginning, he considers both source material and methodology; he analyzes the problems of writing history and notes the fallacies which most frequently lead historians astray. His comments are still relevant today.

Another aspect of Ibn Khaldun’s originality is his stress on studying the realities of human society and attempting to draw conclusions based on observation, rather than trying to reconcile observation with preconceived ideas. It is interesting that at the time Ibn Khaldun was writing, the humanist movement was well under way in Europe, and it shared many of the same preoccupations as Ibn Khaldun, in particular the great importance of the interaction between people and their physical and social environment.

One of Ibn Khaldun’s basic subjects is still being debated, and it is of the greatest relevance in the increasingly multicultural societies of today: What is social solidarity, and how does a society achieve it and maintain it? He argues that no society can achieve anything—conquer an empire or even survive—unless there is internal consensus about its aims. He does not argue in favor of democracy in any recognizable form (which suggests he may not have had intimate knowledge of the Greek political theorists), and he assumes the need for strong leadership, but it is clear that, to him, a successful society as a whole must be in agreement as to its ultimate goals.

He points out that solidarity—he uses the word ‘asabiyah—is strongest in tribal societies because they are based on blood kinship and because, without solidarity, survival in a harsh environment is impossible. If this solidarity is joined to the other most powerful social bond, religion, then the combination tends to be irresistible.

Ibn Khaldun perceives history as a cycle in which rough, nomadic peoples, with high degrees of internal bonding and little material culture to lose, invade and take resources from sedentary and essentially urban civilizations. These urban civilizations have high levels of wealth and culture but are self-indulgent and lack both “martial spirit” and the concomitant social solidarity. This is because those qualities have become unnecessary for survival in an urban environment, and also because it is almost impossible for the large number of different groups that compose a multicultural city to attain the same level of solidarity as a tribe linked by blood, shared custom and survival experiences. Thus the nomads conquer the cities and go on to be seduced by the pleasures of civilization and in their turn lose their solidarity and come under attack by the next group of rough and vigorous outsiders—and the cycle begins again.

|

|

|

Figure 5a-b: Two posters from the exhibition Encounter of Civilizations: Ibn Khaldun displayed at the United Nations Headquarters in New York (18th December 2006-17 January 2007). (Source). |

|

Ibn Khaldun’s reflections derive, of course, from his experiences in a radically unstable time. He had seen Arab civilization overrun in some parts of the world and seriously undermined in others: in North Africa by the Berbers, in Spain by the Franks and in the heartlands of the caliphate by Timur and his Turco-Mongol hordes. He was well aware that the Arab empire had been founded by Bedouin who were, in terms of material culture, much less sophisticated than the peoples of the lands they conquered, but whose ‘asabiyah was far more powerful and who were inspired by the new faith of Islam. He was deeply saddened to watch what he saw as a cycle of conquest, decay and reconquest repeated at the expense of his own civilization.

As Ibn Khaldun developed his themes through the Muqaddimah, he presented many other innovative theories relating to education, economics, taxation, the role of the city versus the country, the bureaucracy versus the military and what influences affect the development of both individuals and cultures. It is in these themes that we find echoes of al-Mas‘udi’s Kitab al-Tanbih wa al-Ishraf, where he considers the factors that shape a nation’s laws: the nature of authority and the relationship between spiritual and temporal powers, to name only two.

It is worth remembering that, besides having witnessed a particularly turbulent period of history, Ibn Khaldun also had much practical experience of politics on both national and international levels. Furthermore, his various terms of duty as a qadi in Cairo gave him, as he claimed, insight into the problems of battling corruption and ignorance in a cosmopolitan environment, mindful of the “moral decadence” he believed to be one of the great threats to civilization. His conclusions were, as he tells us in his Autobiography, based on practical knowledge and direct observation, as well as academic theory.

It would be hard for any book to live up to the standard set by the Muqaddimah, and indeed Kitab al-‘Ibar does not. Although it is an invaluable source for the history of the Muslim West, it is less remarkable in other fields, and Ibn Khaldun did not share al-Mas‘udi’s lively and unbiased interest in the non-Muslim world. Other blank spots are all the more surprising in that Ibn Khaldun was living in Cairo with access to excellent libraries and bookshops.

On the other hand, there were occasions when he made great efforts to establish facts accurately. It must have required courage to ask Timur himself to correct the passages in the ‘Ibar that referred to him! Timur was of great interest to Ibn Khaldun, who hoped the conqueror might be the one to provide the social solidarity needed for a renaissance of the Muslim and, especially, the Arab worlds—but it was a short- lived hope.

Ibn Khaldun wrote a number of other books on purely academic subjects, as well as early works which have vanished. His Autobiography, although lacking personal details, contains extremely interesting information about the world in which he lived and, of course, about his meetings with Pedro and Timur.

Ibn Khaldun’s strength was thus not as a historian in the traditional sense of a compiler of chronicles. He was the creator of a new discipline, ‘umran, or social science, which treated human civilization and social facts as an interconnected whole and would help to change the way history was perceived, as well as written.

|

|

Figure 6: Two coins issued in 1382 during Antonio Venier reign as Doge of the Venetian Republic from 1382 to 1400. Antonio Venier was responsible for reviving Venice’s economy after the Black Death and negotiating with the Mamluks to make the city Egypt’s most important trading partner. At this period, Ibn Khaldun was resident in Cairo. The statue is displayed in the Real Alcázar’s Hall of the Ambassadors, where Ibn Khaldun may have been received by Pedro I. (Source). |

4. The Exhibition Ibn Khaldun: The Mediterranean in the 14th Century: The Rise and Fall of Empires

The exhibition marking the 600th anniversary of the death of Ibn Khaldun could not be held in a more evocative place than Seville’s Real Alcázar (Royal Palace). Not only is it a most beautiful backdrop, but it is a building that Ibn Khaldun himself knew. He walked through the same rooms where the exhibition is being held today, and he stood in the great Audience Chamber when he met Pedro I “The Cruel” on his peace mission from the sultan of Granada in 1364.

That is, of course, if the rooms were complete, for in 1364 the palace was partly under construction by the Christian king “in the Moorish manner,” decorated with Arabic calligraphy by Muslim craftsmen in the style called mudejar. For Ibn Khaldun it must have been a strange experience to revisit the city where his ancestors had held high office and to walk through older areas of the palace, such as the Patio del Yeso (Patio of the Stuccoes), which they would have known.

Opened by King Juan Carlos and Queen Sofía of Spain and attended by royalty and dignitaries from many countries, the commemorative exhibition is dedicated to the world of Ibn Khaldun, placing him in the context of his age and doing much to explain his particular preoccupation with the rise and fall of empires.

Apart from manuscripts, some in his own hand, and his sister’s tombstone, little survives that is directly connected with Ibn Khaldun, although the writings of his friend Ibn al-Khatib are represented. Nevertheless, from around all the Mediterranean, a dozen or more countries have contributed items to build up the picture of the material world he would have known: plates such as those he might have used, mosque lamps, a traveler’s writing box, a set of nesting glasses, some beautiful examples of Granada silk and more.

In one section of his Autobiography, Ibn Khaldun wrote at length about the gifts he arranged to be sent to certain rulers on various occasions. These were an essential part of the diplomatic exchanges of the day, and fine silks played an important role. He also described his hunt for suitable presents to give Timur: He chose a one-volume copy of the Qur’an with an iron clasp, a pretty prayer rug, a copy of a famous poem (al-Burdah) and four boxes of his favorite Egyptian sweets—which he tells us were immediately opened and handed round. Similar items are on display.

The world of Ibn Khaldun is also brought alive by photographs or architectural details of buildings he would have known, from the street on which he is believed to have lived in Tunis to the Castle of Ibn Salamah, now in ruins, where he retired for four years of relative peace to write his great work. The madrasahs, where he taught all across North Africa and in Cairo, are represented too—including, of course, al-Azhar, the great center of Islamic learning still functioning today.

The Christian world is also present to remind the visitor of what was going on in Europe in terms of art and intellectual achievement during the period Ibn Khaldun was writing. There are objects from China and Central Asia too, for besides the struggles for power among the Berber dynasties in North Africa and the Christian attempt to drive the Muslim colonizers from Spain, the great threat to civilization as Ibn Khaldun saw it was in fact posed by Timur. Hence the Central Asian steppe was an important part of the world picture from which his theories of the rise and fall of empires was formed. Taking advantage of Seville’s warm summer nights, the exhibition stays open until midnight. This enables visitors to wander through the courtyards of the palace, watch the moon reflect in the ornamental pools and inhale the scent of jasmine—a plant introduced by the Arabs and which Ibn Khaldun would have known.

In the evenings, a play about Ibn Khaldun is performed in the gardens, and across the façade of the palace there is a striking play of projected images: knights in armor, Mamluk horsemen, depictions of Dante and Timur, calligraphy in both Arabic and Latin, maps and landscapes taken from illuminated manuscripts.

One of the most remarkable achievements of this exhibition is its fine catalogue, coordinated under the auspices of the Granada-based El Legado Andalusí and the José Manuel Lara Foundations. It is in two volumes, with one dedicated specifically to the exhibition and the other a compilation of articles on aspects of Ibn Khaldun and his world written by scholars from a wide range of universities. (Fittingly, Ibn Khaldun’s home city of Tunis is particularly well represented.) It is, in fact, an anthology of the most up-to-date scholarship on Ibn Khaldun and his world.

|

|

Figure 7: Map of the Muslim World around 1400, few years before Ibn Khaldun’s death. In the 15th and 16th centuries, three major Muslim powers emerged: the Ottoman Empire in much of the Middle East, the Balkans and Northern Africa; the Safavid Empire in Greater Iran; and the Mughul Empire in South Asia. These new imperial powers were made possible by the discovery and exploitation of gunpowder, and a more efficient administration. (Source). |

Particularly interesting is the analysis of his manuscripts by Jumaâ Cheikha of the University of Tunis, who shows that the oft-repeated statement that Ibn Khaldun was not valued in the Muslim world is untrue: 195 surviving copies of his various books may not seem like much in the light of modern print runs, but by medieval standards it indicated success. Many works by more recent authors have come down to us in not more than a single copy.

As an homage to Ibn Khaldun, and one that would surely have given him pleasure, the organizers and especially Jerónimo Páez López, founder of El Legado Andalusí, have gone to immense trouble to ensure that places associated with Ibn Khaldun are all represented and different aspects of his world covered. It is very much to be hoped that the plans for the exhibition to travel to a number of different locations will come to fruition.

5. Appendixes [2]

5.1. The Black Death

“Civilization both in the East and the West was visited by a destructive plague which devastated nations and caused populations to vanish. It swallowed up many of the good things of civilization and wiped them out. It overtook the dynasties at the time of their senility, when they had reached the limit of their duration. It lessened their power and curtailed their influence. It weakened their authority. Their situation approached the point of annihilation and dissolution. Civilization decreased with the decrease of mankind. Cities and buildings were laid waste, roads and way-signs were obliterated, settlements and mansions became empty, dynasties and tribes grew weak. The entire inhabited world changed. The East, it seems, was similarly visited, though in accordance with and in proportion to [the East’s more affluent] civilization. It was as if the voice of existence in the world had called out for oblivion and restriction, and the world responded to its call” (tr. Rosenthal).

5.2. The Contents of the Muqaddimah

1. Human society, its kinds and geographical distribution.

2. Nomadic societies, tribes and “savage peoples.”

3. States, the spiritual and temporal powers, and political ranks.

4. Sedentary societies, cities and provinces.

5. Crafts, means of livelihood and economic activity.

6. Learning and the ways in which it is acquired.

5.3. The New Science

“This science then, like all other sciences, whether based on authority or on reasoning, appears to be independent and has its own subject, viz. human society, and its own problems, viz. the social phenomena and the transformations that succeed each other in the nature of society…. It seems to be a new science which has sprung up spontaneously, for I do not recollect having read anything about it by any previous writers. This may be because they did not grasp its importance, which I doubt, or it may be that they studied the subject exhaustively, but that their works were not transmitted to us. For the sciences are numerous, and the thinkers belonging to the different nations are many, and what has perished of the ancient sciences exceeds by far what has reached us” (tr. Issawi).

5.4. Overcrowding and Urban Planning

“The commonest cause of epidemics is the pollution of the air resulting from a denser population which fills it with corruption and dense moisture…. That is why we mentioned, elsewhere, the wisdom of leaving open empty spaces in built-up areas, in order that the winds may circulate, carrying away all the corruption produced in the air by animals and bringing in its place fresh, clean air. And this is why the death rate is highest in populous cities, such as Cairo in the East and Fez in the West” (tr. Issawi).

5.5. The pernicious effects of domination

“A harsh and violent upbringing, whether of pupils, slaves or servants, has as its consequence that violence dominates the soul and prevents the development of the personality. Energy gives way to indolence, and wickedness, deceit, cunning and trickery are developed by fear of physical violence. These tendencies soon become ingrained habits, corrupting the human quality which men acquire through social intercourse and which consists of manliness and the ability to defend oneself and one’s household. Such men become dependent on others for protection; their souls even become too lazy to acquire virtue or moral beauty. They become ingrown. …This is what has happened to every nation which has been dominated by others and harshly treated” (tr. Issawi).

5.6. Taxes

“In the early stages of the state, taxes are light in their incidence, but fetch in a large revenue; in the later stages the incidence of taxation increases while the aggregate revenue falls off. …Now where taxes and imposts are light, private individuals are encouraged to actively engage in business; enterprise develops, because businessmen feel it worth their while, in view of the small share of their profits which they have to give up in the form of taxation. And as business prospers the number of taxes increases and the total yield of taxation grows. However, governments become progressively more extravagant and start to raise taxes. These increases [in taxes and sales taxes] grow with the spread of luxurious habits in the state, and the consequent growth in needs and public expenditure, until taxation burdens the subjects and deprives them of their gains. People get accustomed to this high level of taxation, because the increases have come about gradually, without anyone’s being aware of exactly who it was who raised the rates of the old taxes or imposed the new ones. But the effects on business of this rise in taxation make themselves felt. For businessmen are soon discouraged by the comparison of their profits with the burden of their taxes, and between their output and their net profits. Consequently production falls off, and with it the yield of taxation. The rulers may, mistakenly, try to remedy this decrease in the yield of taxation by raising the rate of taxes; hence taxes and imposts reach a level which leaves no profit to businessmen, owing to high costs of production, heavy burden of taxation and inadequate net profits. This process of higher tax rates and lower yields (caused by the government’s belief that higher rates result in higher returns) may go on until production begins to decline owing to the despair of businessmen, and to affect the population. The main injury of this process is felt by the state, just as the main benefit of better business conditions is enjoyed by it. From this you must understand that the most important factor making for business prosperity is to lighten as much as possible the burden of taxation on businessmen, in order to encourage enterprise by giving assurance of greater profits” (tr. Issawi).

5.7. At Qal‘at ibn Salamah

“I had taken refuge at Qal‘at ibn Salamah… and was staying in the castle belonging to Abu Bakr ibn ‘Arif, a well-built and most welcoming place. I had been there for a long time…working on the composition of the Kitab al-‘Ibar to the exclusion of all else. I had already finished drafting it, from the Introduction to the history of the Arabs, Berbers and the Zanatah, when I felt the need to consult books and archives such as are only to be found in large towns, in order to check and correct the numerous citations that I had set down from memory. Then I fell ill…. Because of all this, I felt a great wish to be reconciled with the Sultan Abu al-‘Abbas and to go back to Tunis, the land of my forefathers, whose houses and tombs are still standing and where traces of them are still to be found” (tr. Caroline Stone).

[1] [The exhibition was held in the Real Alcázar de Sevilla in May-September 2006: Ibn Jaldu´n: el Mediterráneo en el siglo XIV. Auge y declive de los imperios [Ibn Khaldun: The Mediterranean Region in the XIV century; the rise and fall of empires] organised in (Sevilla by the Fundacio´n El Legado Andalusi´ and Fundacio´n Jose´ Manuel Lara [note added by MuslimHeritage.com editorial board].

[2] These extracts from Ibn Khaldun’s Muqaddima are part of the article published in Saudi Aramco World. A note in the article specifies: “Where not otherwise credited, translations from the Muqaddimah are from Charles Issawi’s An Arab Philosophy of History: Selections from the Prolegomena of Ibn Khaldun of Tunis (1332–1406)(revised edition 1987, Darwin Press) or from Franz Rosenthal’s three-volume translation The Muqaddimah(second edition 1967, Princeton University) [note added by MuslimHeritage.com editorial board].

* Caroline Stone has published more than 150 articles over the years in various languages, principally on textile history, medieval history and literature, Islamic culture and literature, and the cultural and economic relations between Europe and the Orient in the pre-modern era. She is the author, with Paul Lunde, of Al-Mas’udi, The Meadows of Gold: The Abbasids, translators and editors (Kegan Paul International, 1989). For a list of her publications, click here. [Note added by MuslimHeritage.com editorial board.]

Razdari ki Fazilat o Ahmiyat

Ottoman Music Therapy

Music has been used as a mean of therapy through the centuries to counter all kinds of disorders by various peoples. Physicians and musicians in the Ottoman civilization were aware of the music therapy in continuation of previous Muslim similar practices. There are numerous manuscripts and pamphlets on the influence of sound on man and the effect of music in healing, both in works on medicine and music. Ideas of Al-Farabi, Al-Razi and Ibn Sina on music were followed by several Ottoman physicians. This article presents a study of music as a therapeutic mean by Ottoman medical authors, and presents comprehensive information on their use of the effects of music on man’s mind and body.

1. Introduction

Is music an efficient means of healing? Can disease be hindered by melodies? Music has been used as a means of therapy through the centuries to heal all kinds of diseases and disorders by various peoples, in spite of discussions about it. Turkish communities have also been practicing music therapy since the pre-Islamic era. Kam, the Turkish shaman tried to get into relation with the spirits of the other world by means of his or her davul, the drum and oyun, the ritual ceremony; hence they tried to benefit from their supernatural powers. The kamtried to affect the spirits by utilizing music, either driving evil spirits away, or attracting the help of good spirits so as to achieve treatment.

We find Ottoman books and pamphlets on the influence of sound on man and the effect of music in healing, both in works on medicine and music. Ideas of Al-Farabi, Al-Razi and Ibn Sina on music were followed by several Ottoman writers such as Gevrekzade (d. 1801), Şuuri (d. 1693), Ali Ufki (1610-1675), Kantemiroǧlu(Prince Dimitrie Cantemir, 1673-1723) and Haşim Bey (19th century). The study of music by these writers as a therapeutic means and comprehensive information given by them on the effects of music on man’s mind and body note the existence of interest and curiosity on the subject during the Ottoman period. Ottoman medical writers such as Abbas Vesim (d. 1759/60) and Gevrekzade offered music to be included in medical education, along with mathematics, astronomy and philosophy, as in order to be a good physician one ought to have been trained in music. This recalls us that music had been included in the quadrivium, the Latin curriculum taught at universities until the late Middle Ages and whih included arithmetic, geometry, astronomy and music.

2. The theory of music therapy

According to the earliest Turkish sources, the cosmos was created by the word kü / kök, the order of the creator, that is by means of sound. This means that the initiation of the cosmos was started by sound. This is an expression of the Creator’s sound coming down and the “Godly sound approach” that is found in cultures of various ancient peoples. This being in accordance with the Islamic belief, which is based on several verses in the Koran, “when He decrees a thing, He only says to it ‘Be’, and it is” (Qur’an, Bakara 2/117). The Turkish peoples’ idea on the divine character of sound was reinforced after conversion to Islam from the 11th century on. The belief that God was comprehended through words and sound being perceived as letter, the essence of existence was believed to be “sound”. The number and differences of letters were related with the variety in the creation and existence. Hence, words were believed to be the cover of essence. This relation played an important part in fostering the belief that music therapy might re-establish the upset harmony of the patient, creating a sane balance between body, mind and emotions.

|

|

Figure 1: Painting by Gaye Özen depicting the Ottoman physician Serefeddin Sabuncuoglu during treatment with his pupils. The figure also depicts music therapy and cauterization by a physician. Picture copied by the permission of Nil Sari. Source: Amasya Selcuklu Osmanli mimarisi ve bezemeleri, edited by Nil Sari, Gülbün Mesara, and Ü. Emrah Kurt (Istanbul 2007). |

In pre-Islamic Turkish music theory, there was a different melody for each day of the year; in addition there were nine melodies which were to be played every day; and specific melodies were to be played during certain hours of the day. That is, the time of the day was an important factor to be respected in playing music. Although the pre-Islamic Turkish calendar, its calculations, and the pre-Islamic Turkish cosmology differed from the Islamic ones in some respects, the traditional Uyghur Turk’s nöbet, the turn of playing before a sovereign or ruler, was a stable tradition which continued as a symbol of sovereignty in the Seljuk and Ottoman period. The mehter music is the best evidence of this.

Muslim scholars appropriated the ancients musical theories and information related with therapeutic music, which can be traced back to the Hellenistic sources, borrowed mainly from Sumerian, Babylonian and Egyptian concepts, perspectives and mysticism. While Muslim Turks traced the ideas of the ancient people, being a part of the Islamic society, they at the same time acted as the main transferors of the Chinese and Indian, that is far eastern ideas to the Near and Middle East and especially to Anatolia, meanwhile introducing their original concepts of central Asian music therapy tradition. These were being reflected specially in Sufi rituals, the zikr.

The ancient theory of numbers and harmony of spheres, that is the motion of the stars, their intrinsic properties, and their effect and influence on mankind, the scheme of cosmic music were reflected to Islamic, hence Ottoman music theory. The theory of numerology expressed in musical terms was developed by Pythagoras, who was influenced by Babylonian astrology. Ottoman writers too “related sound to the cosmos through a mathematical conception of sound vibrations connected with numbers and astrology.” The inaudible sounds produced by the movement of celestial bodies, called the “harmony of the spheres” were believed to express the mathematical harmony of the macrocosm. Hence, modes, or sequences of musical notes were believed to have a mathematical meaning. “The search for reason and intellectual logic in music therapy depended on the idea that man was a part of the universal harmony.” Just as celestial bodies were believed to have counterparts in the human body, sound vibrations as a reflection of celestial bodies as well, were supposed to affect a diseased part of the body. Attaining harmony between body and soul led to health.

3. Ottoman Turkish music modes as a mean of therapy

Patients suffering from a certain illness or the emotions of persons with a certain temperament were expected to be influenced by specific modes of music. Certain makams, that is musical modes, were prescribed for therapeutic purposes. Makam is “a concept of melody which determines tonal relations, as well as an overall indication of the melodic patterns.” Modes, as patterns of organized sounds, were believed to express special meanings. Though there are about 80 Turkish modes; usually only 12 were prescribed for therapy, in accordance with the limitation of the related theories of cosmic elements and numerology, as it is in the Islamic and ancient sources. From the old texts we can deduce the kind of music which was supposed to cure a certain disease or create certain feelings and favour certain behaviours; though the musical modes of those days are not the same as those that we know today.

The aims of Ottoman music therapy by playing specific modes prescribed for certain physiognomies and nations can be classified as: treatment of mental diseases; treatment of organic diseases; maintaining/re-establishing the harmony of the person – a healthy balance between body, mind and emotions by pleasing him/her; leading the way to emotions, such as getting people laugh or making them cry etc., preventing vicious feelings and attracting good ones, training the self and thus reaching perfection.

|

|

Figure 2: Painting by Nil Sari depicting the treatment of an insane patient by musical therapy. Inspired from the scene in Figure 1. |

The writers who regarded music as a means of treatment seemed to attribute a lasting value to its effects. That is, the effects of the music applied systematically as a preventive or curative means on physical and mental state were stated as predictable; for example, the musical mode rast was supposed to be therapeutic for the paralyzed. Others were believed to cause sleeping, sadness or joyfulness or motivated intelligence etc. Thus, some produced effects of relaxation, or soothed the soul, others caused excitement etc. While illness, that is the lost balance of the four humours was tried to be restored by means of music, the temperament and physiognomy of the patient also had to be observed and valued. This meant that, although there were modes of music which were means for healing specific illnesses, the best suitable mode could be reached in accordance with the response it could elicit from the patient, which was supposed to depend on his or her temperament.

It is interesting that musical modes were believed to have power on physical processes and functions as well as the moods and emotions as a whole. That is, the responses to music were supposed to have both physical and emotional effects. Those who suffered from anxiety, insomnia, indigestion, paralysis, dysuria etc. were all expected to be treated and cured through the effect of suitable music. For example, sciatica was expected to be treated by nevâ, an Ottoman musical mode. Even malicious infections were recommended to be treated by musical modes, which can be traced back to the antique ideas of Democritus. For example, Ottoman writers advised the mode hüseyni against fevers, and the musical modes zengule and irak for the treatment of sersam, that is meningitis. Then being incurable, what was the purpose of music therapy applied for treating malicious infectious diseases? Was it only a theory?

Was music used merely as a means for pleasing patients? Or, was music regarded as an imaginary substitute for a dysfunction or misbehavior? Today we know that “music contains suggestive, persuasive or even compelling elements, specially depending on the harmonies present in any particular sound.” But, how was it explained? “Did writers/physicians presume that music influenced the emotions and created moods which in turn acted on the body; or did it work in reverse, from the body to the psyche? ” Today we know that “most of the time the two processes react on each other;” and that “even without cortical involvement sound can arouse the activities of the autonomic nervous system.” Ottoman physicians and musicians of the 17th and 18th centuries were not informed of modern physiology and psychology, but were aware of the body-mind interaction. The manifestations of the autonomous nervous system have been observed through the ages since ancient times. We find evidences of it both in literature and illustrations, displaying the influences of music on various parts of the body or specific organs, mainly the heart. The physiological responses to musical vibrations could not be measured, but changes in the cardiac and respiratory processes, that is heart beats and breathing were described. Today we know that emotional impact of music may provoke certain involuntary physiological responses, such as changes in blood circulation and breathing. It is also a fact that the heart is an organ whose function is deeply effected by emotions.

Above all, rhythmical patterns together with a melody have been used through the ages as a means of stimulating muscular action, that is physical activity. The Ottoman band of musicians of the palace, the mehterwas also used to enhance and built up physical energy on the way to war.

|

|

Figure 3: A music therapy scenario from Edirne History of Medicine Museum. |

4. How was music therapy applied?

As we learn from the Book of Travels (1664) of Evliya Çelebi and the Adjustment of Temperaments by the physician Şuuri (d.1693), treatment by music therapy was through listening; and music therapy in Ottoman hospitals was not practiced as one – to – one relationship, but a group of patients listened to a group of players and singers, that is music therapy was probably a collective activity. But, if in theory its effect was supposed to differ from one temperament or illness to another, it must have been practiced on members of a group of specific temperaments or diseases. Whether or not or to what degree practice depended on theory is a matter of discussion not solved so far. There is no description of the way of application by music therapy in Turkish texts; only advises were made for treating illnesses, without any detail such as the distance between the patient and the player or singer. Nothing is noted in medical works about the healer and his or her relationship with the patient, and no mention is made of whether patients played instruments or not.

|

|

Figure 4: A miniature picture depicting an insane patient during a musical therapy session at the Bayezid II’s Hospital. Picture copied by the permission of Nil Sari and Ulker Erke from: 38th International Congress on History of Medicine, Turkish Medical History Through Miniature Pictures Exhibition. (Drawn by U. Erke, organized and edited by Nil Sari), Istanbul 2002. |

In Ottoman medical manuscripts dealing with music therapy, we find only the prescription of special modes to be used for certain illnesses. Music therapy was speculative, but it was used empirically, too. There is no mention of religious healing or the use of music as a means of communication with the supernatural world, and cure through the divine intervention. Music therapy is not stated in medical manuscripts as a faith therapy of supernatural origin, but was rationalized by being based on the theory of four elements and humours. Scholarly medical writings of the Ottoman period being on the same lines with Hippocratic teaching, had a rational attitude to illness and made use of music as a method of rational healing. However, there is almost no criticism of the kind we come across frequently in medical books about the different evaluations of the humoral theory and practices in accordance with it. There seems to have been no need for discussion in the prescribed musical modes and their effects. This impresses one as scholastic information transferred through centuries. It should also be noted that only some of the medical works of the Ottoman period include chapters on music therapy, though medical subjects of the day are regularly included in all of the medical books. I wonder if music therapy was not considered as a subject of discussion, because it was not regarded as an inevitable method of therapy.

In spite of the detailed information about the time- in which day of the week and which hour of the day which musical mode should be played to which temperament, I have not come across knowledge about how long the therapy should be continued, except for a 16th century trust of deed of Tire, an Aegean district, which notes that the insane should be treated by listening to songs and instrumental music for two hours in the afternoon. But, there is no detail about how many times it should be repeated. However, detailed tables that show the days and times when and to which temperament musical modes should be played, were formed. Since the same modes and temperaments are cited several times, so we may assume that music therapy was expected to be repeated at certain intervals, that is it was a cure to be continued so long as needed.

5. Appropriate use of music as a mean for developing one’s self

Patients’ responses to or effects of music therapy is not noted in the sources studied, except by Şuuri of the 17thcentury. Şuuri describes giving up music therapy at the Bayezit II.’s hospital in Adrianople, as a result of its being regarded as an entertainment by those who spoiled the rules of the hospital and have them neglect their duties, that is, it had been abused and also disturbed some patients. This reflects a critical attitude, though no criticism is found about the success of music therapy. However, this evidence can be taken as an example of music therapy being failed for the time. We may also conclude that in hospitals purely recreational approach to music may not have been considered appropriate. Leader philosophers of the Islam, however, agreed with the idea of using music for recreation, provided it didn’t provoke lust. That is, it was considered improper to let lust overcome the mind by means of music.

The philosopher, the physician and the Sufi, observing that some music modes have joyful and others have saddening influences, they utilized the effects of sounds. It was generally believed that using music’s influence in the right way trained the soul. Ottoman writers on music expected music to be also a means to develop an ideal character. Attaining harmony between intellect and emotions could lead a man to become conscious of himself. We recall that ancient philosophers Plato and Aristotle believed that certain musical modes possessed an ethical value and produced certain effects on the morality of the listener and helped in the development of character.

For the Sufi, purification and enlightenment came through the heart. The heart was described as the most virtuous organ and the symbolic center of man’s existence and the feeling of love felt through the heart was accepted as the key of being aware of the existence of the Creator. This was an educational approach to music. Sufi music was used as a means of training for ideal perfection, which also meant becoming harmonious with oneself. Man, being accepted as the symbol of the universal creation, was described and evaluated as a micro-cosmos. It was believed that all the characteristics of the universe were awarded to man by the Creator. Therefore, the ultimate aim of music was to attain freedom of the self (nefs), so as to reach his/her soul to the divine origin.

|

|

Figure 5: A few scenes by İnci Özen from the Dar al-Shifa of Anbar bin Abdullah during the Seljuk reign in Turkey. The figure is depicting the gate and the music therapy by the physicians. Picture copied by the permission of Nil Sari. Source:Amasya Selcuklu Osmanli mimarisi ve bezemeleri, edited by Nil Sari, Gülbün Mesara, and Ü. Emrah Kurt (Istanbul 2007). |

Khula kay Ahkam o Masail

Praise be to Allaah.

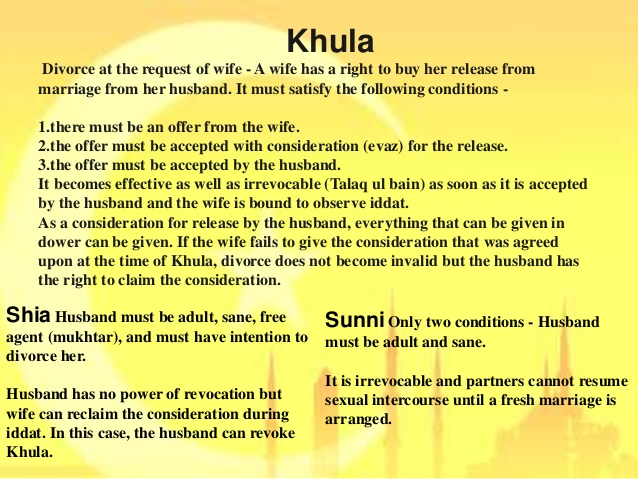

Khula’ means the separation of the wife in return for a payment; the husband takes the payment and lets his wife go, whether this payment is the mahr which he gave to her, or more or less than that.

The basic principle concerning this is the verse in which Allaah says (interpretation of the meaning):

“And it is not lawful for you (men) to take back (from your wives) any of your Mahr (bridal-money given by the husband to his wife at the time of marriage) which you have given them, except when both parties fear that they would be unable to keep the limits ordained by Allaah (e.g. to deal with each other on a fair basis). Then if you fear that they would not be able to keep the limits ordained by Allaah, then there is no sin on either of them if she gives back (the Mahr or a part of it) for her Al-Khul‘ (divorce)”

[al-Baqarah 2:229]

The evidence for that from the Sunnah is that the wife of Thaabit ibn Qays ibn Shammaas (may Allaah be pleased with him) came to the Prophet (peace and blessings of Allaah be upon him) and said, “O Messenger of Allaah, I do not find any fault with Thaabit ibn Qays in his character or his religious commitment, but I do not want to commit any act of kufr after becoming a Muslim.” The Prophet (peace and blessings of Allaah be upon him) said to her, “Will you give back his garden?” Because he had given her a garden as her mahr. She said, “Yes.” The Prophet (peace and blessings of Allaah be upon him) said to Thaabit: “Take back your garden, and divorce her.”

(Narrated by al-Bukhaari, 5273).

From this case the scholars understood that if a woman cannot stay with her husband, then the judge should ask him to divorce her by khula’; indeed he should order him to do so.

With regard to the way in which it is done, the husband should take his payment or they should agree upon it, then he should say to her “faaraqtuki” (I separate from you) or “khaala’tuki (I let you go), or other such words.

Talaaq (i.e., divorce) is the right of the husband, and does not take place unless it is done by him, because the Prophet (peace and blessings of Allaah be upon him) said: “Talaaq is the right of the one who seizes the leg (i.e., consummates the marriage)” i.e., the husband. (Narrated by Ibn Maajah, 2081; classed as hasan by al-Albaani in Irwa’ al-Ghaleel, 2041).

Hence the scholars said that whoever is forced to divorce his wife by talaaq wrongfully, and divorces her under pressure, then his divorce is not valid. See al-Mughni, 10/352.

With regard to what you mention, that a woman in your country might arrange her own divorce through the man-made laws, if this is for a reason for which it is permissible to seek a divorce, such as disliking her husband, not being able to stay with him or disliking him because of his immoral ways and indulgence in haraam actions, etc., there is nothing wrong with her seeking divorce, but in this case she should divorce him by khula’ and return to him the mahr that he gave to her.

But if she is seeking divorce for no reason, then that is not permissible and the court ruling on divorce in this case does not count for anything in terms of sharee’ah. The woman still remains the wife of the man. This gives rise to a new problem, which is that this woman is regarded as a divorcee in the eyes of the (man-made) law, and can re-marry after her ‘iddah ends, but in fact she is still a wife and not a divorcee.

Shaykh Muhammad ibn Saalih al-‘Uthaymeen (may Allaah have mercy on him) was asked about a similar matter and said:

Now we have a problem. The fact that she is still married to him means that she cannot marry anyone else, but according to the court ruling she is apparently divorced from him, and when her ‘iddah ends she can re-marry. I think that the only way out of this problem is that good and righteous people should get involved in this matter, to bring about reconciliation between the man and his wife. Otherwise she has to give him some payment, so that it will be a proper shar’i khula’.

Liqa’ al-baab al-Maftooh by Shaykh Muhammad ibn ‘Uthaymeen, no. 54; 3/174.

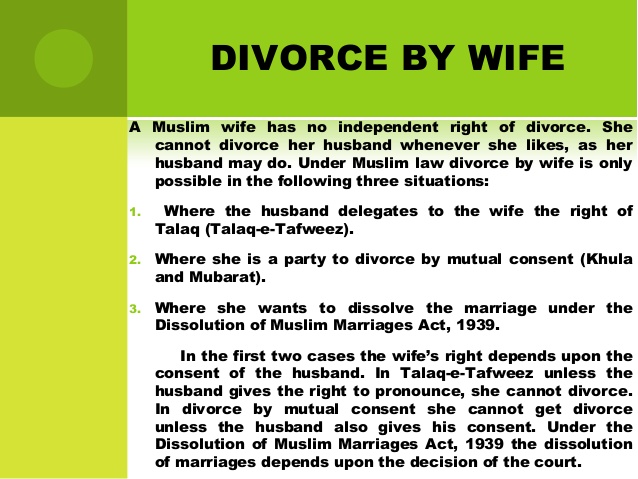

Under Islamic law, divorce can take place in three forms, namely by talaq (repudiation of wife by husband), by khula (by mutual consent) or by faskh (decree of the court dissolving the marriage). It can be said that If Talaq is defined as the right specifically granted to men to divorce their wifes , khula can be said to be its equal for women as it gives them the right to raise it when seeking for a divorce, and even if the men do not accept it, they can refer to the Qadi for help to enforce it.

Khula operates the same way as marriage is concluded in Islam, being by way of offer and acceptance, except this time it is usually the wife that makes the offer of divorce and the husband has a choice of whether to accept it or not. Like how a dowry must be gifted to the bride upon marriage, the wife has to offer some kind of compensation to the husband, as consideration for the husband releasing her from the marriage. Similarly, as in contract law, the wife has the right to revoke this offer as long as before acceptance is made. However this is not the case for a husband relying on this form of divorce, his offer will be to repudiate the wife in return for a certain amount of compensation and this offer of his is not revocable and remains effective until rejected.

The four schools of Sunni Law though divided as to how the Khula doctrine may be performed all agrees that generally under the doctrince of Khula, that in order for the wife to release herself from the marriage, she has to give up some property in return as consideration of the husband granting her a khula, the only exception being that she was subjected to abuse and threats. The value of the compensation is not to exceed the amount of dower that was given to her initially. This is reflected in a hadith where a woman approach the Prophet and told him in return for divorce, she was willing to return more than what was given to her, but the prophet replied, ‘You should not return more than that.’’ The compensation can be anything that is of value but Shafi law holds that is has to be monetary. Nonetheless, once accepted by the husband, the marriage itself is dissolved and operates as a single talaq but it is immediately irrevocable. The only way of reconciling would be to remarry.

As to when Khul can be given, it would be fair to say that the same conditions for talaq are to apply in that the wife has to be in the state of purity. The Hanafis holds to this but the Malikis say this is not necessary as the woman has willingly obtained Khul in consideration of payment, therefore her right to do so even when menstruating. Similarly the Hanbalis is of the same view that since Khula comes about by mutual agreement of the two married partners, there is no harm even if it is given during menstruation.

The very first form of Khula was narrated in the hadith by Imam Bukhari whereby a woman approached the Holy prophet and said that though she shared not animosity with her husband, she wish to separate from him because she feared she could not perform her functions as a wife. The prophet asked if she was willing to give her husband the garden he gave to her as dower and when she agreed, the prophet asked the husband to take back his garden and divorced her at once. From this hadith, we can infer that Khula need not only take in the form of mutual consent but can also be granted by third parties like the Qadi through decree of court, thereby amounting to judicial Khula. If the husband refuses to accept the wife’s offer, she can go to the Qadi and demand a formal separation and the Qadi upon satisfaction of her reasoning for wanting the divorce, may call upon the husband to repudiate her. But where the husband still refuses to do so, the Qadi can himself pronounce a divorce which will operate as valid repudiation and the husband will be liable for the whole amount of the deferred Mahr.

However the granting of Khula by the Qadi is only granted in extreme circumstances, the Prophet warned the women who asked for Khula without any reasonable ground with:

‘’If any woman asks for divorce from her husband without any specific reason, the fragrance of paradise will be unlawful to her’’

The following are the grounds where divorce may be granted by the Qadi:

- Habitual ill-treatment of the wife

- Non-fufillment of the terms of the marriage contract

- Insanity

- Incurable incompetency

- Abandoning the marital home without making provision for the wife

- Any other similar causes which in the Qadi’s opinion justifies a divorce

As can be seen, where Khula is not consented by the husband, the wife has an alternative route to the court. When the matter is brought to court, if it falls under Faskh, she will not owe the husband any compensation but otherwise if she has to do it by way of Judicial Khula, the court will require her to return the compensation to the husband. Even so, Khula or Faskh was never easily applied previously as in the traditional Hanafi law. The Hanafi law has the most restrictive view towards women seeking for dissolution; the only ground acknowledged was if the husband proves unable to consummate. Thus once consummated, she loses her request for dissolution even where the husband fails to support her, abuses her, or is imprisoned for life. The rest of the schools are more open in the sense that they recognized that a divorce may be granted upon other grounds such as those stated above. The Maliki law is the most liberal in that it gives the women the right to obtain a divorce on the ground of dhahar, being harm or prejudice. If she is unable to prove that continuing to be with her husband is causing her harm but insist that a discord existed between her and her husband, the Maliki court will reconstruct itself into an arbitration tribunal. Two arbitrators will be appointed, one being a representative from the wife’s family and the other from the husband’s. Their mission together with the Qadi would be to reconcile the spouses but if unsuccessful, they will hear evidences from both side and determine who is primarily responsible. If it is the husband, they will pronounce an irrevocable talaq on his behalf and if it the wife, they will pronounce a repudiation in return for the giving of compensation by the wife to the husband.

Over the then years reforms have been introduced to extend the rights of wife to divorce through the inspiration of the Maliki law. In India, the Dissolution of Muslim Marriage Act 1939 extended the earlier mentioned grounds for divorce to include other grounds such as where the husband has been missing for four years, the husband having been imprisoned of seven years or more, the husband was impotent at the time of marriage and repudiation by wife who married before she was 15 before attaining the age of 18 and provided the marriage had not been consummated. In Pakistan, The Muslim Family Law Ordinance 1961 added on to the extended list with a further ground being when a husband takes a second wife without complying with the provision of the Ordinance. Soon later, in the case of Khurshid Bibi v Mohammed Amen, the Supreme Court of Pakistan recognized another form of dissolution by recognising the role of Judicial Khula that now allows wives in Pakistan to petition for it on the grounds that the marriage had broken down irretrievably but provided the court was satisfied that the parties could no longer cohabit together within the limits prescribed by Allah. However, more recently in the case of Naseem Aktar V Mohammad Rafiq, where the argument was that the wife failed to prove the alleged hatred was dismissed by the Apex court and held that the fact she applied for dissolution was sufficient evidence of hatred and aversion, thereby not requiring to prove that it was impossible to cohabit with her husband and the court must grant a Khula. In addition, in a more liberal approach in Aurangzeb v Gulnaz (actually goes against the whole concept of Khula), the court held that even if the wife refused to return the dower, the marriage would be dissolved once the Family Court decided that the parties could not remain together.

Similarly the law of divorce in Egypt had been reformed to recognize Judicial Khula in the event where mutual consent cannot be obtain, the wife can bring the matter to court and the wedding will be dissolved upon her returning her dower to the husband. However before the divorce is granted, the court must attempt to bring about a reconciliation within the next three months but after which the wife still formally declares that she cannot live with her husband within the bounds prescribed by Allah, the marriage will be dissolved and the judge will have no discretion to refuse the divorce.