Imam Abu Mansur Al Maturidi as the faithful successor of Imam Abu Hanifa.

The heresiographies, remaining silent does not necessarily mean that Al-Māturīdī was entirely neglected or passed over in the pertinent medieval Literature. On the contrary, there are two other genres of sources in which observations on his doctrines are to be culled; these even provide a specific interpretive image to his name. Yet in order to properly categorize these representations of Al-Māturīdī, one must first consider the geographical and temporal Circumstances in which they emerged and were conveyed. The first remarks on our theologian naturally originate from the region in which he was active, namely, Transoxania. When reflecting on the nature of their theological tradition, scholars of that region from the fifth/eleventh century held that it had been decidedly imprinted by al-Māturīdī’s contributions. This is the sense of the testimony given by Abū l-Yusr al-Pazdawī (d.493/1100)[1] for instance, and by his younger contemporary Abū l-Muʿīn al-Nasafī (d.508/1114), who expressed the same thoughts even more pronouncedly[2]. Neither of them, intended to identify al-Māturīdī as the founder of Sunnī theology in Transoxania, however. To them he was rather an outstanding representative of the same; not as a founder, but as a thinker who masterfully laid out and interpreted a long-standing theological doctrine. Instead, they were in agreement on placing Abū Ḥanīfa (d. 150/767) at the original genesis of the school. He was remembered as having provided the correct answers to all definitive questions in matters of faith, and what he taught is supposed to have been transmitted and elaborated upon by all his successors in Bukhārā and Samarqand without detectable alteration.

In the writings of al-Pazdawī, this position is expressed in two ways. First, he calls his own school, not the “Māturīdīya,” but deliberately aṣḥāb Abī Ḥanīfa [3]. Having said this, he repeatedly endeavors to reiterate to the reader that one or another particular doctrine had, of course, already been professed by Abū Ḥanīfa[4]. Al-Nasafī’s remarks are even more explicit and systematic. He does not merely rely on the fact that the great Kufan is cited by name in northeastern Iran every now and then. His goal was to prove that Abū Ḥanīfa’s doctrine had in fact been passed on from generation to generation intact and without interruption. To that end, he used the topic of God’s attributes as an instructive example, writing what was to be understood as an affirmation of tradition and a program for the future: Al-Nasafī begins this with the statement that in the entirety of Transoxania and Khurāsān, all the leading figures of Abū Ḥanīfa’s companions (inna aʾimmata aṣḥābi Abī Ḥanīfa . . . kullahum) that followed his way in the principles (uṣūl) as well as the branches ( furūʿ), and that stayed away from iʿtizāl (i.e., the doctrine of the Muʿtazilites), had already “in the old days” held the same view (on God’s attributes) as he did[5]. In order to prove this, a historical digression follows, in which names of earlier prominent Ḥanafites of Transoxania are listed. In this presentation, al-Nasafī describes the history of the Samarqand school, running through a contiguous chain of scholars with apparently equivalent theological perspectives. This chain begins with Abū Ḥanīfa, continues with Muḥammad b. al-Ḥasan (al-Shaybānī), and continues through the ranks on to al-Māturīdī and his successors[6]. Al-Māturīdī is viewed in this presentation as a member—albeit a prominent one of a homogenous series of theologians. His merit is supposed to have come from advocating theological doctrine in a particularly brilliant and astute manner; this was a doctrine, however, that all the other scholars followed in principle as well. Because of this, al-Nasafī repeats in several places that al-Māturīdī always deferred to the statements of the school founder from Kufa[7] and when he praises al-Māturīdī it is with the honorific of “the most knowledgeable person on the views of Abū Ḥanīfa” (aʿraf al-nās bi-madhāhib Abī Ḥanīfa)[8].

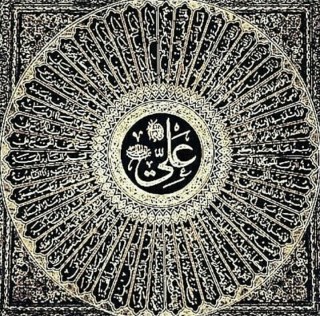

It is noteworthy that we can detect an apologetic undertone with al-Pazdawī as well as with al-Nasafī. This was directed at the Ashʿarites of Nishapur, who had apparently censured the Transoxanians for allowing unacceptable innovations in their theology. At the focal point of this critique was the doctrine of divine attributes professed in Samarqand and the surrounding areas. This was denounced by the Ashʿarites as a heretical innovation of the fifth/eleventhcentury that none of the predecessors (salaf ) had adhered to[9] Such a critique, however, was obviously easy to disprove on a historical basis: It was undeniable that al-Māturīdī had been active at the turn of the fourth Islamic century, contemporaneous with al-Ashʿarī, one might add[10]. An even more convincing counter-argument aimed to antedate al-Māturīdī: If Abū Ḥanīfa stood behind the entire Transoxanian theological tradition, then the circumstances could be explained and vindicated from every doubt: in this light, the aṣḥāb Abī Ḥanīfa of Samarqand not only adhered to proper doctrine, but could maintain its legitimacy through the important Islamic principle of historical seniority. Admittedly this apologetic argument did not promulgate any entirely novel view of things, but for this same reason it must have been viewed as cogent and rather plausible, given the established custom which stood behind it. Indeed, Abū Ḥanīfa’s name had been cited in Transoxania in this manner for a long period of time. Already by the third/ninth century, texts named him as the highest authority, and al-Māturīdī, too, did not fail to demonstrate his reverence for him in many instances[11]. Thus if al-Pazdawī and al-Nasafī pointed to the great Kufan as the actual authority of Transoxanian theology, this was not decisive for Abū Ḥanīfa’s lauded status, but rather against al-Māturīdī’s, or to be more precise, against the conceivable possibility of selecting him as the new leader and eponym of the school. His emergence did not signify a break in the teachings of faith; his doctrine was in no way a new paradigm. What really mattered was the tradition itself, and by paying homage to this tradition arose the image of Abū Ḥanīfa as school founder, with Abū Manṣūr al-Māturīdī as his brilliant interpreter.

Once this decision was taken, it gained credency in times to follow. It is thus unsurprising that we commonly read in later literature about the Abū Ḥanīfa-school of northeastern Iran. Ibn al-Dāʿī, for example, a Shīʿite author of the sixth/twelfth century, relates that the theologians of Transoxania of his time are Ḥanafites with determinist leanings[12]. Tāj al-Dīn al-Subkī (d. 771/1370) described the doctrine of the Māturīdīya two hundred years later, saying that it was the doctrine of aṣḥāb Abī Ḥanīfa[13]. Even the Ottoman scholar Kamāl al-Dīn al-Bayāḍī (d. 1078/1687), committed without a doubt to al-Māturīdī’s ideas, also rotely cited the same tradition: His main theological work bears the title Ishārāt al-marām ʿan ʿibārāt al-imām, and states after just a few lines that the foundation of all religious knowledge is to be found in the articulations of the “leader of leaders” (imām al-aʾimma), i.e., Abū Ḥanīfa[14].

[1] Abū l-Yusr Muḥammad al-Pazdawī, K. Uṣūl al-dīn, ed. Hans Peter Linss (Cairo, 1383/1963), 2.-2ff. Hereafter cited as Uṣūl.

[2] Abū l-Muʿīn Maymūn b. Muḥammad al-Nasafī, Tabṣirat al-adilla, ed. Claude Salamé (Damascus, 1990–93), vol. 1, 358.15 ff. Hereafter cited as Tabṣira.

[3] Uṣūl, 190.9.

[4] On the doctrine of attributes (ibid, 70.11f.); on human capability for action (ibid., 115.14ff.); on the concept of belief (ibid., 152.6ff.).

[5] Tabṣira, vol. 1, 356.6–8.

[6] Ibid., vol. 1, 356.8–357.9.

[7] For example, ibid, vol. 2, 705.9ff. And 829.1f.

[8] Ibid., vol. 1, 162.2f

[9] Ibid., vol. 1, 310.8ff. compare also al-Pazdawī’s reaction, Uṣūl, 69.10ff. and 70.5ff. On this General theme, see Rudolph, “Das Entstehen der Māturīdīya,” ZDMG 147 (1997): 393–404.

[10] The chronological comparison with al-Ashʿarī must have played a role in the polemic, as Tabṣira, vol. 1, 240.8ff. shows, where it is explicitly stated that al-Māturīdī adhered to a particular doctrine that was only later adopted by the Ashʿarīya.

[11] Cf. Abū Manṣūr Muhammad b. Muḥammad al-Māturīdī, K. al-Tawḥīd, ed. Fathalla Kholeif (Beirut, 1970), 303.15, 304.1, 369.21, 382.19 [ hereafter cited as Tawḥīd]; idem, Ta’wīlāt al-Qurʾān, ed. Ahmet Vanholu (Istanbul, 2005), vol. 1, 81.8, 105.7, 121.8, 158.10, 193.8, 231.1, 343.11, 354.4, 369.14, 393.2, 408.5 and many others (cf. the indices of the other volumes) [hereafter cited as Taʾwīlāt].

[12] In Ibn al-Dāʿī, K. Tabṣirat al-ʿawāmm fī maʿrifat maqālat al-anām, ed. ʿAbbās Iqbāl (Tehran, 1313/1934), 91.9: “Ḥanafiyān-i bilād-i Khurāsān u-kull-i mā-warāʾa-nahr u-Farghāna u-bilād- Turk jabrī bāshand.”

[13] See the following section.

[14] Kamāl al-Dīn al-Bayāḍī, Ishārāt al-marām min ʿibārāt al-imām, ed. Yūsūf ʿAbd al-Razzāq (Cairo, 1368/1949), 18.5f. with an enumeration of works attributed to Abū Ḥanīfa (in this edition, page 18 is the first page of text of theIshārāt).

→Note:- The above passages are taken from the book, “Al-Māturīdī and the Development of Sunnī Theology in Samarqand” by Sir Ulrich Rudolph, Pg 7-9.